Are they an equal art? The new long-form TV and feature films?

This question is presented to me often but in a different form. As Chief Film Fan at the Indie Film Minute, I am often asked, “Are you going to start covering some of the great new TV?”

First, a little history.

When TV first started coming on strong, there was great worry in the film community. Would TV replace feature films?

That early worry faded quickly, as it soon became clear that TV was a very different thing than film. Film, at its best, told thoughtful stories. TV of the time was generally pablum—a great way to pass time, often with a laugh along the way.

Now, don’t get me wrong, TV can be important. There is nothing wrong with a quality TV show that simply helps a viewer see the silly side of life. Interview shows bring insight into the world around us, and on Oprah, sometimes you could even win a car!

And TV, with its unmatched market saturation, has helped society evolve in such important ways.

Off the top of my head, an early example of a show with cultural importance would have to be All In The Family, with Archie Bunker illuminating the evil foolishness of a full flight of societal illness. By bravely scrapping the scab off of festering societal wounds, healing was advanced.

Modern Family, ABC

And examples of progress through television continue today. Ellen DeGeneres in Ellen and Mitch and Cam on Modern Family helped dispel society’s prejudices against the LGBT community by portraying gay characters as likable, normal, contributing members of society. By introducing these relatable characters into our homes, TV took the lead in bringing acceptance to a segment of our society that had too often been painfully relegated to the shadows.

Whether we’re talking about simple entertainment or shows of societal importance, TV has played and still plays an important role in our world. It deserves respect. But the question of which is the higher art emanates from a new phenomenon: that of intelligent, long-form, scripted stories presented on the small screen.

Perhaps this started back in 1977 with Roots, the ratings phenomenon that rocked the TV world of its time. It was an ambitious production, presented in eight segments, that personalized the pain and reality of slavery in America. This was quality scripted TV and people responded.

But long-form TV took a giant step forward when cable came into its own. With big budgets and lots of time to fill, these channels were ready to try something new. In 1999, HBO launched a little mafia story called The Sopranos. Slowly and surely the phenomenon grew. The writing was superb. The plots subtle and intelligent. The abundance of time allowed for character nuance and development. Many of the elements that make great films great were incorporated—season after season.

And the big talents of the film world started to take notice. Hollywood was well into their tent pole strategies, with fewer films (and therefore fewer opportunities for talent to express itself) and less subtlety and intelligence. Sure, the indie world existed as a place for intelligence, where talent and audience were respected. But their budgets were always constrained. And Oh! What allure there was with a larger palette.

The Original Godfather Part II Screenplay, Eippol

As a feature film is crafted, each page, each sentence, each instant of a script must be analyzed. With each page contributing one minute of time to a finished film, there is simply no room for unnecessary detail. A mindful feature film is proven to be most audience-acceptable at a length between 90 and 120 minutes. With this in mind, every element must be probed as the filmmaker considers the question “Does it deserve to be on the screen?”

It takes great skill to get it right, and beloved elements of every story are always left to waste in service of the film as a whole.

How alluring it must be for a storyteller to have time as an extravagance. Subtle elements of character have time to reveal themselves. Images of detail can linger on the screen, enhancing their psychological effect. And with the broadened palette of programs that cable provided, projects could be targeted to a thinking and appreciative audience—smaller, to be sure, than that of the mindless TV of the past, but significant both in financial and cultural context.

As this new long-form TV came into its own with quality project after quality project, talent that used to look down on “the lesser art” started opening themselves up to the smaller screen. Top actors, screenwriters, and directors started coming on board.

Yes, much of what we love about film is now delivered to us in larger doses, over many hours, on long form TV. We have the great stars participating, and an opportunity for under-appreciated character actors, who now regularly prove themselves well primed for larger roles, to reveal themselves to an appreciative public.

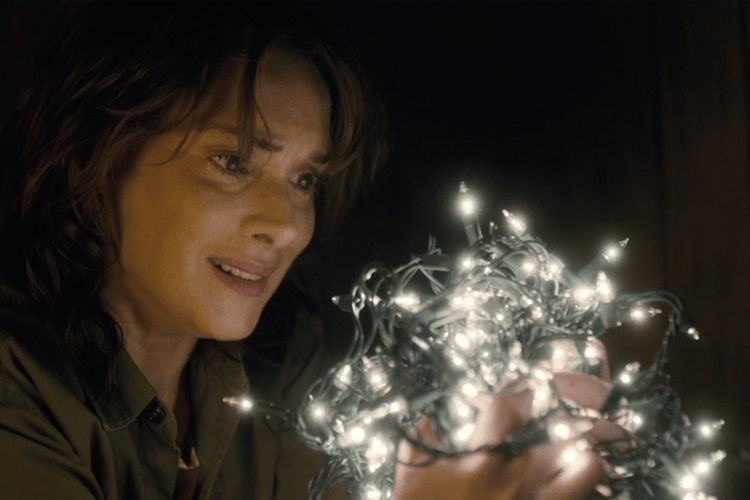

Winona Ryder in Stranger Things, Netflix

But let us return to the basic question. Which is the higher art? The new long-form TV or the old clearer champion, feature films?

I believe that the answer lies in the power of effect that the ultimate experience delivers. In long-form, though there are moments that land with ultimate power, the effect of the story is blunted through long-form delivery. Sure, there remains satisfaction in a story well told, but in long-form it is different. Where a feature film takes its audience on a fast and furious journey, long-form meanders, delivering great detail perhaps, but at the cost of immediacy and therefore impact.

Coffee vs. Tea.

So to me, the answer—without serious deprecation for the lesser of the two—lies in the severe discipline needed to accomplish a feature film that really works. You see, without the luxury of time, a story must be distilled to its essence. It is just much harder and therefore indicative of greater skill and painful discipline to make a feature that works. But when a film works, it hits the senses with a power and impact that is unmatched. An awesome power that leaves its audience changed. A power enhanced by the limitation of brevity.

So while we are all blessed by the new long-form storytelling, we must retain our respect for and participation with feature films, for they are different in important ways, and with certainty, the highest art of our times.